This series of articles began with a brief primer on the history of social alarms and telecare and was followed by an overview of the current care technology landscape in the UK. We went on to discuss how technology enabled care is changing due to the adoption of digital technologies – including, the move away from reactive alarm-based services to data-rich approaches that enable more supportive and preventative service models to be developed. The changing landscape of communications technologies was then considered taking into account the digital transformation of the UK’s telecommunications networks and its effect on the telecare sector. New and alternative approaches to providing digital connectivity between devices and care services were introduced. In our previous article, we considered how the role of monitoring services will evolve to accommodate the shift to cloud-based applications and the increasing use of data in technology-enabled care services. We describe this as a fifth generation of telecare moving beyond the current fourth generation of digital systems being deployed.

In this article, we will consider how all these changes will impact on the way that services are delivered, with improved outcomes for end-users, service commissioners, and providers. We discuss the need for a holistic approach enabled through interoperability and introduce the concept of a unified data model enabled through a ‘meta’ platform. We go on to consider how such an approach might transform services using use-case vignettes of fictional characters and comparing current mainstream approaches with new and emerging digital applications.

The leap to digital

The current focus of the technology-enabled care sector is on the digital transformation of telecare alarm services and their migration from legacy analogue infrastructure to new digital IP-enabled hubs and monitoring platforms. This offers technical futureproofing with respect to the digitisation of telecommunications networks and mitigates problematic communications issues during the analogue to digital switchover period. It achieves this at the cost of introducing new challenges regarding how power and data link redundancy are supported – as discussed in a previous article. However, many of these new digital hubs merely replicate the alarm functionality of their analogue counterparts, which they are replacing. They are relatively ‘dumb’ devices; most do not support the collection of data that would enable even third generation care technology applications and services to be supported, let alone 4G or 5G services. Moreover, many of the first tranche of digital alarm hubs don’t fully enable the transition to IP, with SIP and the latest encryption technologies not always supported. The risk for commissioners is that there will be a need to invest in upgraded digital alarm hubs to replace their existing first-generation digital alarm hubs once newer models are released that fully support the latest industry standards. The same can be said of the peripheral devices that link into digital alarm hubs – these do not support the collection of data, even if they are similar to sensors used in 3G+ data-led care technology applications. These devices use proprietary protocols to transmit alarm codes to the alarm hub – they are not comparable with the IoT sensors that are used with 3G+ products and which send on the underlying data for analysis. It is also worth noting that some suppliers have updated their in-home wireless technology to allow for bidirectional communication, some alarm hubs offer backwards compatibility with legacy peripherals, whilst others require new peripherals to be purchased (due to a change in the operating frequency used).

It may be apparent therefore that this approach does not offer service-level futureproofing, as it essentially provides a like-for-like replacement in terms of product and service functionality, with some additional benefits, mainly for service providers. In other words, the reactive alarm-based service model remains. These like-for-like digital upgrades do not support the kinds of advanced applications that are currently in their infancy, but which might be expected to mature rapidly in the not-too-distant future – i.e. those that use data to help support people in their day-to-day lives and which offer preventative interventions prior to situations deteriorating to the point at which an alarm response is required.

The amount of data that can be easily monitored now using IoT-based sensors placed in the home, wearable devices, interactive surveys, and other approaches, means that a rich picture of an individual’s needs and wellbeing can be established. These data can support applications and services which might help individuals every day and therefore be perceived as being more useful to end-users and their families compared with previous generations of sensors that are limited to alarm-based capabilities that are, by their very nature, used infrequently and seen as an ‘insurance’ against worst-case scenarios. The data sets available with next-generation sensors and platforms can be augmented with relevant information from the Internet of Things to build services that offer true value to users (providing “everything” of use). Furthermore, because devices can always be connected to the ‘cloud’, the coverage offered by new digital applications is far better than that of traditional telecare systems, which are primarily limited to the home. In an era of smartphones and mobile connectivity, this seems to be a significant limitation. Increasingly, support is available to people outside of their homes, allowing them to be independent when out and about in their communities (hence, “everything, everywhere!”).

A brave new world?

“If I had asked my customers what they wanted they would have said a faster horse.” – a quote often attributed to Henry Ford, in relation to his development of the motor car in the beginning of the 20th century (although there is no evidence to support this attribution). It is used to highlight the distinction between identifying a problem or need and choosing a solution – with an assumed bias favouring familiar and established approaches. The lesson it is used to teach is that sometimes a leap of faith is required – a shift to a completely new way of thinking… a solution that does not simply replicate or improve the existing way of doing things, but which completely reimagines a way of solving the problem, Figure 1.

As we have discussed in previous articles in this series, there is currently a parallel world of technology-enabled care, one where people have moved away from the alarm-based model and are embracing the data-led approach. The numbers are currently relatively small, but they are growing, and will eventually overtake the prevailing alarm-oriented model. The sooner this transformation can occur, the sooner the benefits of such systems can be realised, with corresponding positive outcomes for all stakeholders. There are many providers of such data-focussed systems and services. All offer comparable functionality, using similar sensors, and offering some variant of a data dashboard with alerting capabilities. They use a variety of technology stacks (as discussed in our previous article on the changing communications landscape of technology-enabled care and illustrated in Figure 6) and the choice of connectivity and hub provider can significantly influence the overall investment required. This is influenced by the complexity of installation and the level of support required, the range/scope of sensor expansion, and the data and system integration capabilities.

Product differentiation is not always easy but could hinge on the efficacy of the data analytics and machine learning algorithms deployed, and the usefulness and ease of use of the monitoring platform and associated dashboards. Establishing the former is not trivial, as methods of comparison are ill-defined and false classifications are not always exposed for evaluation. Additional features beyond the core data monitoring capabilities include tablet-based touchscreen user interfaces that support interactive questionnaires, video communications and other apps, voice assistants, acoustic analysis, smart home integrations and support for medical monitoring. Their ability to integrate with other third-party applications and systems may also prove to be decisive in how well they are adopted in the long-term.

For service commissioners and providers, the commitment to migrate to these platforms relies on a leap of faith until the evidence of their success is apparent. This includes changing service models from one centred solely around an alarm monitoring centre towards a distributed model that includes the end-user, supported with smart care technologies as well as the direct involvement of family members, friends and other responder agencies, Figure 2.

There will also undoubtedly be winners and losers in this product category; supplier consolidation is inevitable. Other than how to ensure that the best provider is chosen to meet current and anticipated needs, another pertinent question is how best to deploy these new digital services using the best mix of consumer-based products and more specialist products and services? How will data from different ecosystems be made available to providers so that they can support individuals using a holistic approach? … and thus enabling, “everything everywhere, all at once!”. What level of interoperability is required, and available, to help make this approach a valuable and long-term undertaking? While data-led monitoring products from multiple suppliers will make use of generic ‘white-label’ sensors and peripherals, the way in which they code and process the data to obtain meaningful insights will be very different. This provides challenges when attempting to assure the future viability of such data and the services that are built on it. The need for an agreed standard coding scheme for data obtained from such systems for care technology applications is highly desirable. Related to this is how will continuity of data be assured if, and when, a particular supplier withdraws from the market? – as, for example, when the 3Rings product was closed-down in March 2019. How can such platforms be withdrawn ‘gracefully’ protecting both the physical assets and the valuable data collected? Will suppliers guarantee to support a product for a specified period?

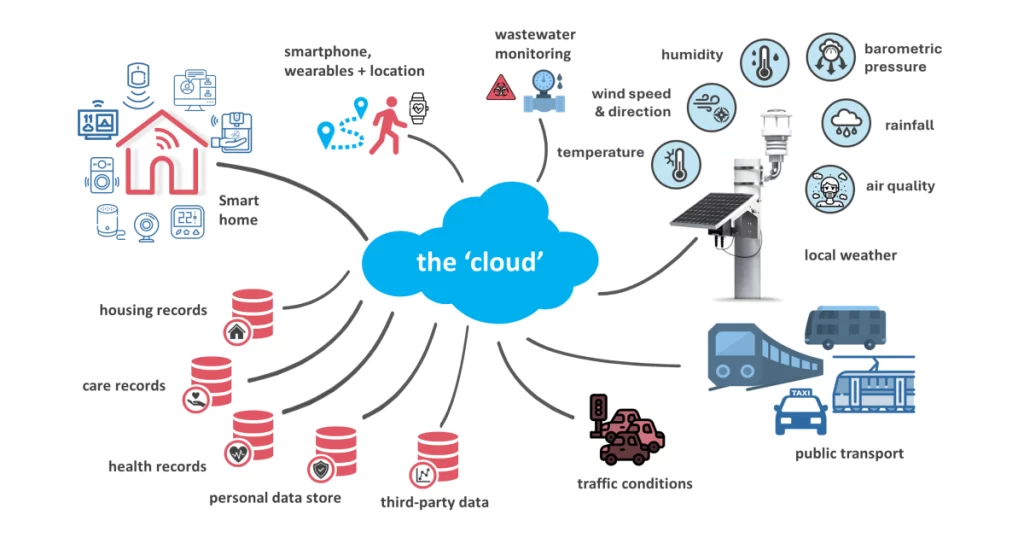

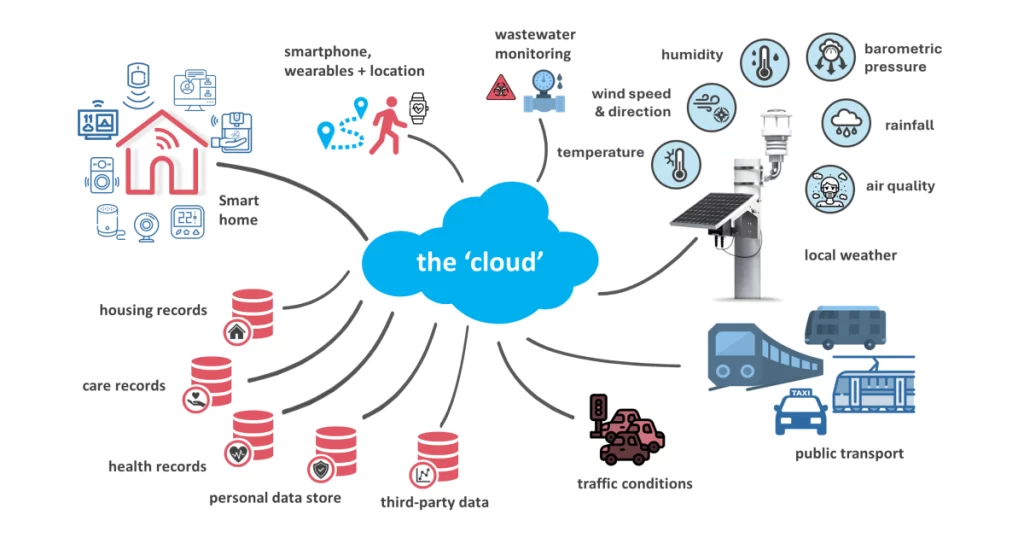

Additionally, there is a need to be able to incorporate useful data from, and integrate with, external third-party sources – such as smart products (tablet/smart speaker/voice UI), specialist devices (e.g. smart medication dispensers/‘robots’), digital records (e.g. health, care, housing, etc.) and other ‘live’ data sources such as those made available using the Internet of Things (IoT). The latter might include local weather and environmental monitoring stations (for data on air pollution or localised flooding) as well as integration with smart city initiatives. The latter could include data on local traffic conditions and the status of public transport, and even wastewater monitoring (for epidemiological monitoring of viral infections such as Covid-19), Figure 3. The ability to share outcome and other relevant data with other health, care and housing providers and commissioners would help to close the loop of care.

Finally, there is scope to move beyond supporting individual users, by enabling (anonymised) population-based monitoring so that global effects can be observed and monitored to help establish locality-focused needs and help plan the development of new services.

Building a unified data model

The question is how all these data sources can be incorporated into a single source of truth – a unified data model, such that it can be used to support truly integrated data-led services. It is impracticable to have to switch between platforms, which in any case would not then offer the opportunities afforded by having a single holistic data platform. There is therefore a requirement for a unifying platform capable of accepting data from disparate sources and linking with other third-party platforms – a ‘meta’ platform (i.e. ‘everything, everywhere… all at once!’). In our previous articles we discussed the types of data that might be considered – this includes both monitored ‘real-time’ or continuously updated data, as well as static records, including the examples shown below:

| Monitored/‘real-time’ data | Static records |

| Home-based activity monitoring and environmental data Health tracking data (from a wearable) Additional wellbeing responses to a prompt/questionnaire (from a smart device or through proactive calling) Location data from wearable/smartphone Physiological data (from medical devices/telehealth) Public IoT devices/applications for additional context & useful information e.g. public transport, local traffic conditions, weather, wastewater, etc. |

Telecare alarm service records Electronic patient records Social care records Homecare agency records Housing management records Medication prescription/ administration records |

Ideally this would be totally vendor and technology agnostic – allowing full ‘whole-of-market’ interoperability for all connected devices. It would also be interoperable with multiple other extended sources of data allowing information to be shared between key stakeholders as required and according to agreed permissions and consents, Figure 4.

Key features of such a platform have been discussed in previous articles, but would broadly include:

- Built using resilient and adaptable cloud-based infrastructure.

- Support TEC sector/open standards and be ‘whole of market’.

- Build applications on a unified data model, supporting sector standard minimum data sets and beyond.

- Incorporate intelligent data analytics and risk models to provide predictive interventions.

- Support rule-based pre-determined and adaptive (learned) alerting capabilities.

- Provide a simple user interface with meaningful and clear data dashboards with suitable levels of abstraction.

- Support an agile approach for a wide range of use-cases for many relevant monitored services from telecare call handling and response logistics, through to video consultations, proactive interventions, user tracking and support, etc.

- It should support skill/availability-based routing to ensure that the fastest most optimal response is always available; and

- It should offer comprehensive outcome & performance monitoring and reporting capabilities.

These could be extended in the future through analysis of speech and image-based footage and even using social media and other digital platforms – although this is likely to be more controversial.

It is evident that such a platform would be a powerful tool, and with such power comes great responsibility! It may be a good place to note that the use of data, when combined from multiple sources, to form a unified model will provide a comprehensive overview of the health and wellbeing of an individual. It is highly sensitive and requires a serious consideration of data protection and related ethical issues, especially regarding the consent of the individual to allow for the collection of, and access to their data.

Although it may be unlikely that any one individual will have all these data sources and records monitored, an individual may have various combinations of such records. The challenge may be for a monitoring platform to be able to manage issues of consent and data access across all the relevant datasets and relevant consumers of this data. Perhaps one solution might be in the form of a personal data store (or vault) in which data is hosted securely from a wide array of sources and which is under the ownership and control of the person being monitored. They can then determine who has access to the data, and importantly, can change permissions as they wish, although this might not be appropriate for all individuals.

In any case, appropriate ethical guidelines should be followed regarding the purpose of any monitoring, and the intended use being made by consumers of such data. Eight elements of an ethical framework for TEC applications are shown in Figure 5 which should inform the design and implementation of such systems.

The meta platform

Let us then review the requirements of such a unifying ‘meta’ platform, a high-level overview of which is shown in Figure 6. Starting at the bottom, it shows how sensors can be used to monitor people, places, and things – and how they interact with each other. Smart home functionality is enabled by devices and controllers that can switch on a light, close a shutter or lock, or unlock a door. This also includes wearable and carried mobile devices that support use outside of the home. Such systems may or may not have a significant user interface component; if they do, it might be through a touchscreen tablet device, voice assistant, smartwatch, or app.

Ultimately these products will be connected to cloud-based services using one or multiple paths including a landline broadband connection, a mobile data connection or a Low Power Wide Area Network (LPWAN) connection, which would negate the need for a local data hub for products situated in the home. It is feasible that there may be more than one of these products or platforms in use (e.g. separate telecare alarm and activity monitoring platforms, Amazon Echo, Fitbit health tracker, blood glucose monitor, etc.).

It is apparent that a layered architecture is needed, starting with a…

- Universal access layer – for connection to products/platforms in the home and on the person. These may have a direct connection or link in using an API . It also supports integration with other platforms and data records as discussed above using API access and the use of sector-wide/open protocols.

- Data layer – a data-aggregation platform that enables a unified data model incorporating relevant data from various sources to enable data-led proactive interventions, support and services.

- Application layer – key features that support the delivery of services.

- Service layer – high level integrated services that are enabled by the layers below.

The goal of a ‘meta’ platform therefore would be to allow access to data from each of these platforms (P1, P2, Pn) using appropriate API access with each. Additional data can be pulled in from extended data sources as required to help build up the unified data model on which to build integrated applications and services. Digital telecare alarms can also be connected using IP alarm protocols. To achieve this, the platform needs to support secure connections over the Internet or through VPNs and SIP for supporting IP Voice services. The ability to export data to external records is also desirable.

Practical applications and impact

How might a unified data model for technology-enabled care change the way in which people are supported? We consider the types of applications that could be provided using two fictional vignettes that compare how an individual might be supported using current approaches vs how they might be helped using linked-up next-generation technologies, with a consideration of the effect on outcomes.

Use case vignette 1: Lorna

Lorna, 82, lives by herself, after her husband of 53 years passed away a couple of years ago. She keeps busy and is reasonably independent but does not drive any more after she gave up her car when it was deemed to be unroadworthy. Lorna has a medical appointment with a specialist to discuss her mobility, as she has stumbled a couple of times recently and fell over when going down the step from her landing into her bathroom at home. At the time, she wasn’t carrying her mobile telecare alarm, which might have automatically detected the fall. She did have her telecare alarm pendant around her neck, but on this occasion, she didn’t feel that she needed to bother anyone. Luckily, she hadn’t badly hurt herself and managed to get up unaided, with only a few bruises and some hurt pride. This event was the trigger for her to ask her GP about her mobility, and the GP arranged for her to be seen by a mobility specialist in her local healthcare clinic.

The morning of her appointment is cold and icy – the salt gritters had been out during the night and some snow had stuck to the roads and the pavements outside her home; they were slippery…

Now…

Lorna’s plan was to catch a bus into town for her appointment. Unfortunately, she was running late – everything took longer these days – so she had to walk a little quicker than usual to get to the bus stop in time for her 9:43 bus, which took her right past the clinic. As she turned on the pavement, Lorna slipped on an icy patch and fell. Thankfully, she didn’t hit her head, but knew immediately that something didn’t feel right. Luckily, she was wearing a mobile telecare alarm with GPS and automatic fall detection. It detected the fall and raised an alarm call through to her monitoring service, where they spoke with Lorna, and to some other members of the public who had come to assist. They called for an ambulance and notified a mobile responder – luckily there was one not far away, so she did not have to wait long for Anna to arrive; she comforted and assessed Lorna – who was in some pain – and established that she may have indeed broken a bone. Anna provided Lorna with a blanket and support for her head. After a wait of about 45 minutes, an ambulance arrived and took Lorna to the local hospital’s Accident and Emergency unit where the triage nurse suspected a fractured hip. The hip repair operation was performed the next day. It was a success, enabling her to be discharged after a few days to her daughter’s home. She would stay there for a few weeks while recovering. The telecare service was notified of her new living arrangements, and they informed her that her alarm pendant would not work until she returned home and to make sure her mobile alarm unit was always within reach when alone in the house. Lorna eventually went back to her own home, but after her fall, her confidence was not what it was, and she didn’t go out as much as she used to.

What if?

Lorna’s Intelligent Support and Lifestyle Assistant (‘ISLA’) – a smart voice-assistant provided by her care technology monitoring service, knew that local weather conditions were bad and that the local transport networks were struggling with the icy conditions. It also knew that Lorna was currently at an increased risk of falling – the activity sensors in her home, and her wrist-worn health tracker, showed that she had slowed down recently and had stumbled a few weeks ago. Data from her health tracker also indicated that her gait was showing signs of imbalance. ISLA was also aware that she was due to attend a mobility assessment clinic this morning. Due to the increased risk of falling due to internal and external factors, ISLA decided to intervene and suggest some options to Lorna…

ISLA knew that the local clinic where she was due to have her scheduled medical appointment supported remote video consultations. So, it explained the situation to Lorna and suggested whether it might be an idea to have her consultation remotely using her smart video care console. Lorna had tried this before, and although it was adequate, she decided she would rather see the specialist in person on this occasion and told ISLA of her preference. ISLA asked how Lorna was planning on getting to her appointment and Lorna decided she would catch a bus – probably the 9:43 bus that took her right past the clinic. ISLA searched to see whether the bus was running on time and established that it was indeed running 12 minutes late this morning. Lorna was pleased to hear this as she was running a little late and was wary of slipping on the icy pavement.

As it happened, just before Lorna was due to leave her house to catch her bus, ISLA caught her attention and let her know that a mobile telecare responder was due to pass her house in the next five minutes and could provide her with a lift to her appointment if she liked. This sounded like a much better option and would avoid the walk down to the bus stop, so she let ISLA know that she would like this. A few minutes later, Lorna answered the door to Anna, a mobile telecare responder, whom she had met before, who escorted her to her car and took her straight to her appointment. Lorna was very grateful, but Anna explained she was heading back to the office anyway and the clinic was on her route. Anna checked with Lorna how she planned on getting back home, and she decided that she’d book a taxi – just in case!

The specialist recommended some strength training to improve her balance and provided her with some details on a local Tai Chi exercise class especially for older people that could be offered as a social prescription. Lorna thought this sounded like a good idea and took up the offer…

Lorna now really looks forward to her Tai Chi classes, and has made a new friend, Sally, with whom she shares many interests, including a love of reading, various TV shows, and cake and coffee! – and they now see each other regularly, independent of the classes. She has also found that her strength has improved and now feels more confident about her mobility.

Use case vignette 2: George

George, 77, lives independently in a sheltered housing scheme, having moved there shortly after his wife died last year. He is overweight, with type 2 diabetes and mild hypertension; both controlled using oral medication. He is prone to bouts of depression and sometimes misses meals and admits that he probably does not drink enough during the day. He used to be a heavy smoker and drinker until he gave up in his mid-50s due to health concerns but has taken up smoking the occasional cigar and enjoys a glass or two of red wine most evenings and the occasional beer at the weekends with his supper. He is prone to respiratory infections. One week in March, George is feeling increasingly under the weather with what appears to be a bad cold…

Now…

George hadn’t been feeling great for a few days. He just couldn’t seem to shift a cough and was feeling a little shaky. Had he taken his medications last night? He wasn’t sure… and he couldn’t remember if he was supposed to skip a missed dose or take extra… George was watching the morning news on the television, although he wasn’t sure why… just endless bad news! Although, he couldn’t really concentrate… he was tired and felt a little drowsy. He’d not been sleeping well recently. He should really make himself some breakfast, but he just couldn’t be bothered. He didn’t really feel like eating … Maybe a little nap would be a good idea…

George woke up startled to the sound of his phone ringing. He answered it and took a while to realise who he was speaking to. It was the telecare service! He realised that he hadn’t pressed the ‘I’m OK’ button on his telecare hub before 10am! No matter, they were always very understanding. He told them that he was fine and had just nodded off after a bad night’s sleep (although he suspected that he was coming down with something). They asked him how his blood sugar readings were – he told them that they were fine (although he’d not taken a reading for several weeks now). He apologised, but they seemed happy enough. He settled down to watch his favourite quiz show on the telly…

The next morning, George felt much worse, and couldn’t get up out of bed. He reached over to find his wireless pendant to raise an alarm for help, but it wasn’t there! He remembered that he had taken it off the other day when Emily, his daughter, had popped over to see him – he never liked admitting that he needed that awful button! He felt too poorly to get out of bed to press the button on the alarm hub downstairs for help; he’d also left his mobile phone in the kitchen to charge overnight. No matter, the telecare service would be in touch eventually after they realised that he hadn’t pressed the button (he looked at his bedside clock – it was 6 am) … in 4 hours!

By the time the monitoring service reached out to him, and received no response, George’s condition had become worse. An ambulance arrived to find him dehydrated and disoriented, and with a bad cough, requiring hospitalisation. He was in hospital for 10 days, waiting for social care to arrange a domiciliary care package when he was discharged. Thereafter, a carer would call twice a day to supervise George taking his medication, and to prepare him his meals. The result was that George could no longer go out for the day. He had lost his independence.

What if?

George was beginning to feel a little under the weather, he’d started coughing the day before yesterday and he just wasn’t feeling himself. He had a few aches and pains and it made it difficult for him to get out of bed and walk to the bathroom first thing. Luckily it seemed to be alright after he’d moved around for a bit.

His ISLA care hub pinged when he entered the lounge – “Hi George, how are you feeling?” It offered him some options to respond, he decided on “Not great!” – he wasn’t sleeping so well, and he felt more tired than normal – and there was this cough. George relied on his ISLA voice assistant – it reminded him to take his medications, when he had appointments, and even to make a cup of tea! That, and his, smart health tracker which he liked because it told him the time, allowed him to ask his voice assistant to play an Elvis song, and let him call for help if he ever needed to – much better than that old alarm pendant he used to have! ISLA suggested that he make himself a drink, but George had just sat down and didn’t fancy getting up right away. The ISLA care hub was connected directly to various devices in his apartment – motion sensors, a kettle-use monitor, and a fridge door sensor. It also had access to information about the ambient conditions in his home, provided by the environmental sensors that the housing association had installed throughout the scheme (including room temperature, humidity and air quality).

ISLA was prompted to ask about George’s wellbeing after receiving an update from his wearable health tracker, which showed how agitated he had been during the night. It also showed that his saturated blood oxygen levels were low, and his breathing laboured. This, together with a significant drop in his usual levels of activity and reduced fluid intake raised an alert that prompted ISLA to check in with George, and to notify the monitoring service.

After a while, ISLA pinged again, “George, would you like me to contact Emily and let her know that you aren’t feeling great?” George thought about it for a while, he would really like to see his daughter, but she was a busy teacher, and he didn’t want to cause her any undue worry – especially at this time of the day. He told ISLA it was fine. ISLA then reminded him to take his morning medication with his cup of tea. George heard but couldn’t be bothered to get up to fetch his tablets from the drawer across the kitchen. ISLA pinged again and said, “George, shall I turn up the heating for a little bit? It’s a little chilly don’t you think?”. It was chilly, but George was trying to reign in his spending, “No thank you ISLA” he replied. He turned on the telly for the news…

ISLA pinged again, “George, Anna from the responder service is going to pop round to see you later this morning at around 11am just to see if you are alright. Is that OK?”. George was fond of Anna, and he was happy to know that he would have some company, he let ISLA know that it would be fine.

Anna was just collecting her coffee from the drive-thru in her mobile response vehicle when she received an amber alert on her car’s smart display. She accepted the task, and asked for details… “George Williams, age 74, requires an urgent wellbeing visit. Activity levels reduced – Significant change in sleep score – Elevated body temperature – Elevated resting HR – Oximetry low – Hydration reminders increased – Acoustic analysis indicates a new and persistent cough – Medical records indicate he is prone to respiratory infections. Average self-reported Wellbeing Index down 26% over past 6 weeks. Ambient environment low temperature alert – Action… Query: Reduced appetite? Query: Infection? Query: General wellbeing? Query: Environmental comfort?”

When Anna arrived at George’s house, he answered the door very slowly and she could instantly see that he didn’t look well. She asked him how he was doing, and he told her about the cough and being off his food and generally feeling under the weather. He also said he was a little down as the anniversary of his wife’s death was approaching. Maybe he wasn’t taking as much care of himself as he usually did. She suggested that he make an appointment to see his GP as she thought that he had a bad chesty cough. She said it would be better to get it sorted before it got worse. He agreed.

Anna asked ISLA to arrange for an appointment with George’s GP surgery. They were linked into the ISLA platform and supported an automated booking system if the data supplied to them indicated that an appointment was advised. George was booked in as a priority to see the GP the next day, where he was provided with antibiotics and advice on rest. His blood pressure was high, and the GP ordered some blood tests. A follow-up appointment was arranged, where the GP informed George that his blood sugar A1C level was significantly increased. The GP altered his medication to address his blood sugar and pressure issues. His medication concerns were noted and addressed using a smart dispensing device for administering his medication with remote supervision by the pharmacy. He was also provided with a blood glucose monitor that automatically uploaded readings to the ISLA platform and referred to a specialist type 2 diabetes support group to assist with his diet, and a local walking club to help with his overall health.

Conclusions

The vignettes presented above show the potential benefits of next-generation care technology platforms that have access to a unified data model, and dispersed care delivery/response services; they include:

- More efficient use of deployed resources (reduced replication/waste).

- Supports individuals to live independently.

- Early detection of health problems and concerns.

- Personalised interventions with context-aware levels of escalation.

- Prevention of adverse effects and incidents.

- Agile and responsive models of support.

- Remote supervision using virtual or distributed care arrangements.

- Proactive health and wellbeing management.

- Joined-up service provision.

- Improved outcomes for user and service providers/commissioners.

The promise of data-led care technology applications will only be fully realised when data from all available platforms and records are made available within a unified data platform. This will support the intelligent analysis and interpretation of events and data that can lead to timely and meaningful interventions. These should support individuals to achieve their goals during their day-to-day lives, whilst also enabling the move away from reactive alarm-based services and towards preventative models of care. The siloed model currently on offer from existing activity monitoring products is not sustainable for the long-term. Only by combining ‘everything, everywhere, all at once’ will a useful holistic approach be possible.

The reality of the current TEC marketplace is that monitoring organisations have grown rapidly in recent years and are likely to work with several different platform providers on behalf of different commissioners, and for individuals and their families. The answer to these challenges revolves around interoperability and the potential for a meta platform to be used that can integrate with all relevant data sources. Such a platform should support holistic service delivery with the best possible outcomes for end-users, their families and service providers and commissioners. A key issue with this approach will be the question of ownership of the data obtained from individual monitoring platforms. If an individual or service provider uses multiple products and platforms to fulfil their needs, then the ability to access all this data to support a unified approach, might not be an option. What then?

Data is often described as ‘the new oil’ – and therefore has an intrinsic value attached to it. Monitoring platforms are typically funded using a combination of capital and on-going subscription-based payments. The latter covers mobile connectivity charges as well as on-going updates and access to a web-based data dashboard with alert notifications. Perhaps one way of tackling this problem is by asserting that the ownership of data about an individual and their home is retained by the individual – irrespective of which platform is used to obtain it. That way they can be in control of how this data is used and shared between different organisations. This raises some practical problems related to how such permissions are obtained, renewed and revoked – but these can be overcome. If multiple platforms are allowed to access data, then the suppliers with the best algorithms and user experience will eventually win through. This might also break the link between data-focussed applications/services and the hardware required to collect the data. To make such solutions cost effective, the ability to share data from sensors installed in the home or on the person, must be a desirable outcome. The need to duplicate devices or hubs in the home at present to support both alarms and monitoring applications is wasteful and inefficient. This leads to the concept of a device-agnostic ‘meta’ monitoring platform.

It may be apparent that most 4th generation monitoring systems, though focusing on digital TEC applications, remain some way off satisfying the requirements for a next generation system proposed in this and our previous article. If monitoring platforms work only within their own siloed data sources, without fully embracing what interoperability means, many of the benefits of a fully integrated digital system will not be realised. The ability to share event notifications between platforms may not be sufficient to support truly integrated applications and services. Such meta platforms should ideally be agnostic to both the sources of data, and to the communication technologies used to collect it. Only then will a universal approach be supported that enables the best possible picture of an individual’s wellbeing and status to be monitored and used to help them live their life to the best of their abilities.

We recommend the development of a robust specification that commissioners and service providers adopt when looking to future-proof their services – whether for service users that are funded by a local authority or are having or choosing to self-fund their care.